Allegiance, the new musical by Marc Acito with music and lyrics by Jay Kuo and which is inspired by stories of Japanese-Americans uprooted from their homes after the Pearl Harbor attack and sent to internment camps, finally arrives on Broadway Sunday. In development for seven years, the show has undergone numerous changes since its 2012 San Diego premiere. Shepherding it to the stage is Olivier Award nominee Stafford Arima (London's Ragtime, Off-Broadway's Bare, Carrie, Altar Boyz).

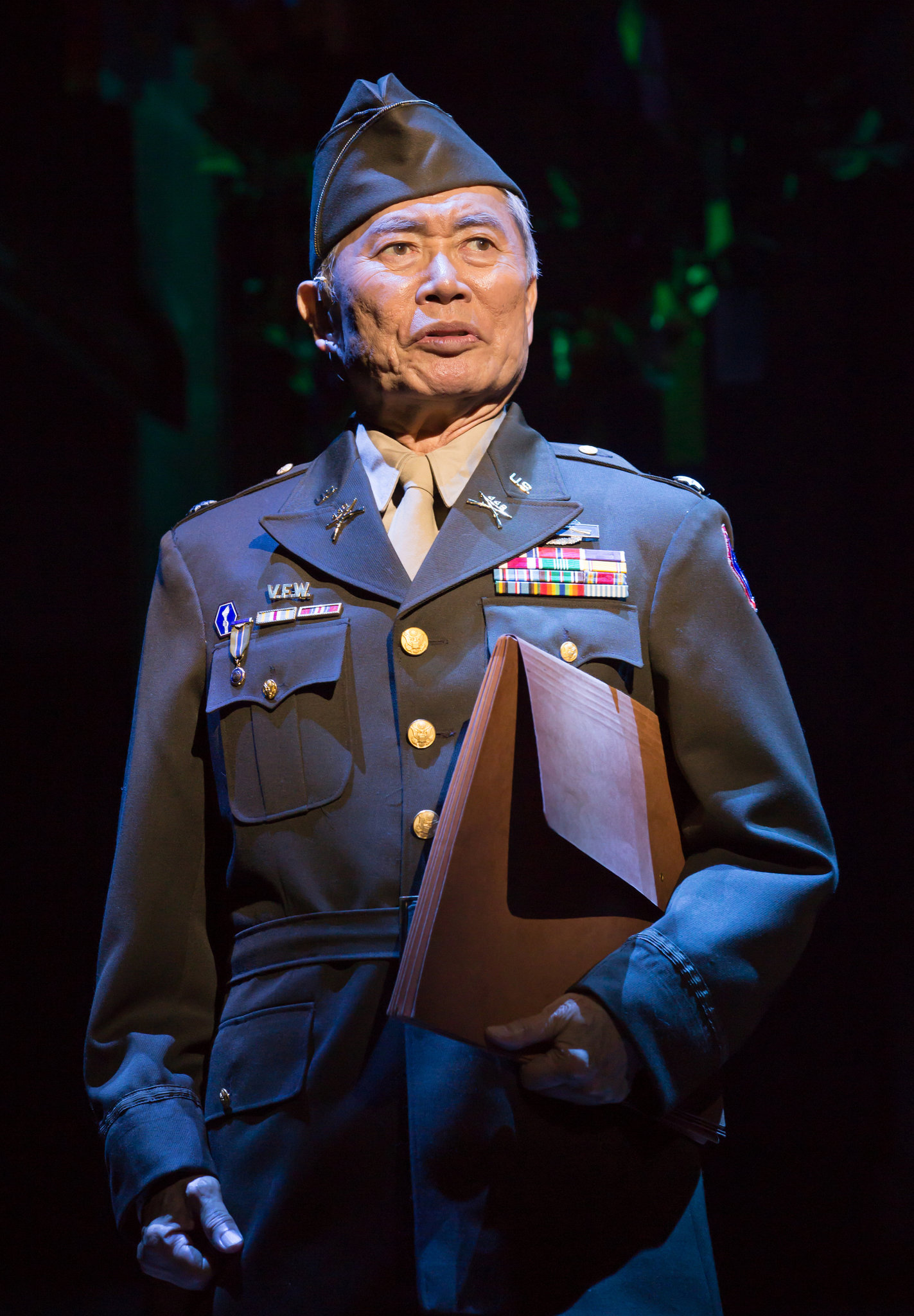

The epic show, which covers six decades, is headlined by George Takei of “Star Trek” fame, who, as a youngster, was sent to internment camps with his family and thousands of loyal Japanese-Americans, Co-starring are Olivier, Tony, and Drama Desk winner Lea Salonga, Telly Leung, and Michael K. Lee. The musical focuses on one loyal American family's extraordinary courage during WWII and the peace time that followed. It's a story of "love, the taboo of interracial love, memory, loyalty, and identity that can motivate and inspire all."

Takei was only five when he saw his life dramatically change. "Early one California morning, I awoke and was looking out the window. I saw soldiers with bayonets mounted on their rifles coming up our driveway. They stormed the porch and pounded on the door. I soon realized that something momentous was happening in my family's life. Overnight we were seen as the enemy, simply because we happened to look like the people that bombed Pearl Harbor.

"I remember how scary it was," he continues. "It was puzzling. None of us were loyal to the Emperor. We were Americans. My mother was born in Sacramento. There were no charges, no trial. We were rounded up and incarcerated in internment camps behind barbed wire fences in the swamps of Arkansas and later California. We lost everything. My father lost his business. We lost our home, our freedom."

Immediately after Pearl Harbor, the 442 division of the Army was created. Thousands of young Japanese men volunteered and went to war to prove their loyalty to America. That division saw fierce fighting and some of the highest casualties of the war.

Through the memories of older Sam (Takei, making his Broadway debut), the story is told of how he (Leung plays younger Sam) enlists in the army as his sister Kei (Salonga) and her boyfriend (Lee) protest the wrongful imprisonment and the draft. Divided loyalties threaten to tear the family apart, "but as long-lost memories are unlocked, they discover it's never too late to forgive and to recognize the redemptive power of love."

Takei says that immigrant issues are very much relevant in today's politics. "When Donald Trump says Mexican immigrants are rapists and criminal with such a broad stroke of the brush, he denigrates all Mexicans—hundreds of thousands who have been here for many generations and are productive citizens. "When 9/11 happened," he continues, "we had attacks on Arab-Americans who'd been here for generations. Then, Japanese-Americans were looked at as the enemy. We've got to learn from history. Unfortunately, this chapter of American history is little known or has been forgotten. So, in an entertaining way, in Allegiance, we remind people of how fragile our democracy is." As a youngster, Takei, who was surrounded in the blocks by those his own age, found a childhood. "Dad told us we were going on a long vacation. It was far from a vacation, but there were good memories. We played in a creek, or as the folks down there called it, a crick. We'd take glass jars and capture pollywogs (tadpoles) and watch them sprout legs and turn into frogs."

Several years later, Takei lashed out at his father over how he allowed the government to put the family in the camps without protest. "I told him that he led us like sheep to the slaughter. He replied, ‘Maybe you're right.' He went into his room and closed the door. I hurt him deeply and, even worse, I never apologized. It has remained one of my biggest regrets. Being in Allegiance and telling this story is one way of saying I'm sorry."

In spite of the degradation and horrible conditions of the internment, Takei says his father "believed in the fundamental ideals of the United States. And this is a man who lost everything. Yet, he was able to define democracy for us as a people's democracy, and said it can not only be as great as the people are, but also as fallible as people are; that our democracy is vitally dependent on people who cherish the ideals and actively engage in the process of a democratic government."

Takei credits his father for shaping the ideals by which he's lived. The actor is most memorably known for his role over three years as Hikaru Sulu on Gene Roddenberry's “Star Trek.” However, he has a storied career in TV and film since the mid-50s when he did English dubbing for Japanese actors in the Godzilla and Rodan monster movies; and has been an outspoken political advocate for gay rights and marriage equality. His family began to put their lives back together at war's end. "When the gates of the camp opened," he remembers, "we were given a one-way ticket to anywhere in the United States and $25. That was it. Everything was taken from us. We were supposed to rebuild our lives with $25. My parents decided to return to Los Angeles. However, the hostility toward Japanese Americans was strong. I learned about prejudice after I came out from the camp. "Finding housing was next to impossible," he adds. "Our first home on reentering society was a hotel room on L.A.'s kid row. It was horrible, frightening. There was the stench of urine everywhere. I had been very sheltered. As a child, the scary people leaning against walls were terrorizing. My father's first job was as a dishwasher in Chinatown." His father was a block manager in the camps, so older Japanese came to him for help and assistance in finding places to live and get work. In a great test of resilience, his father opened an employment office in Little Tokyo. The kind of jobs he was able to find paid a pittance: janitors, dishwashers, gardeners.

"The hostility didn't go away," Takei states. "In grammar school, my teacher Mrs. Ruggen referred to me as a Jap. It hurt. She never called on me when I raised my hand. She hated me, and I hated her right back. As an adult, thinking back, I thought maybe she had a son or husband in the Pacific theater and lost them. I couldn't understand why she treated me as she had. I'd done nothing."

Takei’s father eventually found a dry cleaning shop in Mexican-American-dominated East L.A. One benefit of that was that Takei learned to speak Spanish. "Everyone worked long, hard, killing hours. I'm still astounded how in four years, dad was able to save enough to buy a three-bedroom home in the mid-Wilshire district. That became our new beginning with grammar school and so forth.

"Father had a good sense of business timing," he adds. "As Japanese-Americans were getting back on their feet, he switched to real estate. He was helpful to the community in purchasing homes and businesses. And out of the ruins, he became quite successful."

It was uncommon for the older Japanese-Americans to discuss the camps. "They felt so wounded and ashamed of that chapter in their lives, they never wanted talk about it. Sadly, there's very little in the history books."

It was a long struggle to get an apology and compensation from the United States. In the 70s, a movement began in the Japanese-American communities to get redress. Congress formed a commission. Takei was among those who testified at the hearings. In 1988, President Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act and formally apologized and pledged $20,000 to each family. "That, sadly, was a mere token of what we all lost," says Takei, "but it was a token. I didn't get my check until George H. W. Bush was president. I donated it to L.A.'s Japanese-American National Museum, which tells our story. "

You can visit www.AllegianceMusical.com to read more about, as George Takei put it, "this controversial chapter of American history that we can't be proud of." There's information on the cast and creatives; and you can view episodes of the docu-series on the process of bringing Takei's "Legacy Project" to Broadway, and how the musical's assimilation and immigration themes are as relevant as ever in today's political climate."

In a one-hour interview with Takei, Lea Salonga, and Telly Leung conducted by WQXR Afternoon Drive By personality Eliot Forrest at NY Public Radio WNYC'S Green Performance Space in Tribeca, Takei discussed his three seasons on “Star Trek” and how Gene Roddenberry selected his character's name; prejudice; coming out gay; his career afterward; and the letdown and betrayal by Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger in the California fight for marriage equality.